Today, even the question itself seems blasphemous. Yet, for most of Christian history, the answer was rather negative.

White people in Medieval Europe were aware of black people’s existence, even though this knowledge was akin to that of a Sahara Bedouin about snow. They could get the picture of what black people really looked like, as many churches would have an Adoration of the Magi icon or fresco, with Balthazar painted tar black.

Otherwise, the Medieval European art scene was as white as your typical refrigerator; with people of colour assigned the rare roles of pageboys and the Queen of Sheba (confined mostly to book illustration, and racially vague, for sometimes her skin was painted blue or purple). Albertus Magnus, a saint and scholar of the 12th c., was certain that perfect reason could dwell in the “normal body” only. His ideas had paved the way for black people to be seen as sub-human for the next three hundred years.

It was unimaginable to have a mix of black and white people in a religious painting. The Last Judgement theme was especially difficult. The Apocalypse was supposed to happen to everybody, not just white people. Black people had to be present there and, hence, shown.

Artists didn’t know what to do with black people. The Church was at a loss itself! Were the unfair-skinned supposed to descend to Hell in marching order, given that they were given black skin already? Was soul-weighting to have any meaning for people with black skin at all?

So, artists put the doctrinally awkward population at the back of the queue of the resurrected, hoping it would get sorted out in some natural order during the Apocalypse.

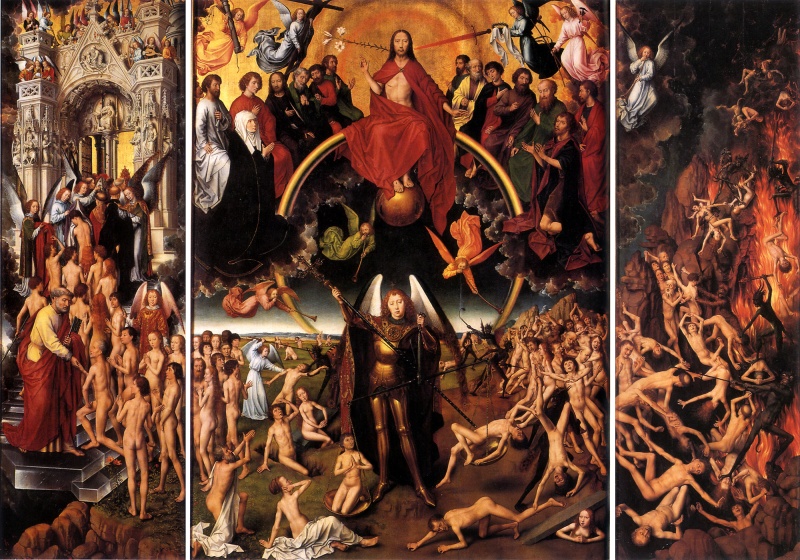

This Judgement Day of 1435 by Stefan Lochner, a German artist who was Durer’s inspiration, is a good example of the trick:

I know it is difficult to see a black man in this work without a magnifying glass. Here he is, barely visible:

What is most remarkable about this painting though – and I can’t miss it even though it takes me off the main track – is its monster community. Each monster is individually unique and mesmerizingly frightening. My favourite is this multi-faced green guy:

Seeing that devilish creature upon resurrection can send a man back to the grave with a heart attack, which is rather ironic. And yes, if you look to the right of the cutie, you’d realise a beer belly takes you to Hell, with the weighting of the soul being no longer necessary. My other fav is the face of the monster relaxing in Hell at the very right corner of the painting:

Look at the different deformities, skin textures, and at the rage and fury of this…yes, BLUE-EYED beast.

I am sorry I have to torture you, says the eye. And sheds a tear.

The breakthrough in the attitude towards black people occurred in 1471, in the work of another German artist, Hans Memling.

This Last Judgement triptych is full of symbolism that has helped many a student obtain top marks for their art theses (I won’t torture you with it, but you can read about it here). While many observers notice two black people in this painting, no one (at least no one I am aware of) has reflected upon the importance of where they were painted. No longer are they queuing at the back. Even though they are not painted at the front, the artist sends one of them to Paradise, while the other is lined up for Hell.

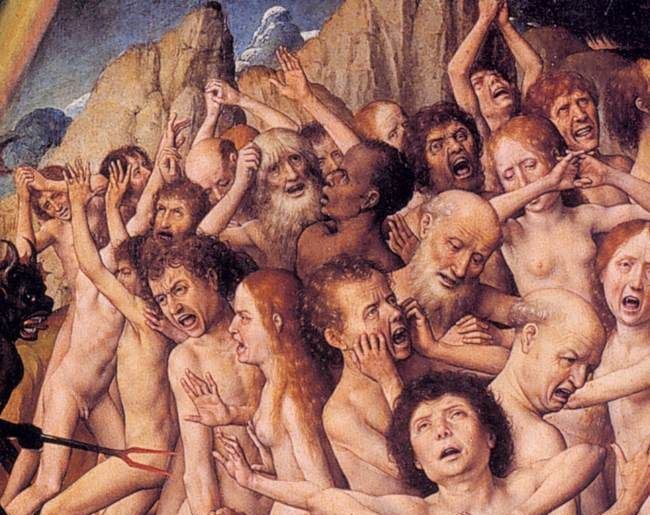

This is the unfortunate black man. He stands among screaming people wriggling with pain and despair, looking up to Archangel Michael with a silent question in his eyes, “What the hell – no pun intended – am I doing here?! Is this just the colour of my skin?!” And indeed, Memling could paint a black man, but he probably had never seen a black man screaming in pain. Do black people tear their hair off? Do they wring their hands? OK, let’s just leave him standing there, wondering what mortal sin he committed. Memling created, inadvertently, the first “WTF” visualisation in art history.

And this is the lucky black man who stands at the back of the crowd herded by angels towards the Gates of Paradise. No rush, there is a whole eternity in front of them.

It is in this painting that black people were recognised to be (a) people, and (b) equal to white Europeans in the eyes of God, perhaps, for the first time, because they were worthy of the weighting of their souls.

I will come back to Memling and this painting over the week. There are many things to enjoy there. Surprisingly, some art critics believe Memling was a lesser artist than Rogier van der Wayden, his predecessor and mentor. This is so not true.

Life was full of mysteries. “Bad things” were those belonging in a different reality, plane, or “hell”. Good things were those brought (if God so wishes) by saints and bishops. It’s almost impossible to think how people saw the world in Medieval Europe. Albertus Magnus described monstrous births and divine signs. Reality and imagination were not as separate as they are today, so we will probably never really understand this type of thinking.

This was really informative and interesting to read. Wow.

Thank you! You may also like my next post on Apocalypse at http://wp.me/p2SuQi-NT ))

Вот здесь любопытный очерк о расизме или вернее его отсутствии в древности: http://bohemicus.livejournal.com/81378.html

Прочитал, спасибо огромное! Но согласиться с автором полностью не могу. Греки, до Македонского (с которого начался этакий космополитизм) были страшными расистами (и не только по отношению к “черным”). Аристотель – первейший идеолог расизма. Даже своего ученика он поучал, что с не-эллинами надо обращаться, как с вещами или животными, обосновывая это расовой неполноценностью.

Я в свое время в юности изучал античную классику. Аристотеля тоже читал много. Но не могу вспомнить ничего про “расовую неполноценность”. У него не-эллин – это варвар, то есть тот, кто обитает по ту сторону всякой идеи о гражданской жизни полиса; а что уже там по ту сторону, в том числе вопрос, как, например, обращаются с рабами (преимущественно покоренными иноземцами) – как с животными или как с членами семьи – это все не важно, потому как суть внутрисемейные, частные, не-гражданские дела… То же самое и с тем, что там происходит за пределами полиса – там просто бескрайний варварский мир, гори он синим пламенем, все это не имеет никакого значения. Так что расизм тут как бы не при чем.

К тому же есть момент правильной интерпретации. Скажем, если Аристо говорит, что одни люди свободны, а другие – рабы по самой своей природе, то тут слово природа совсем не в нашем современном значении употребляется.

Мне надо “обновить” память ) Я согласен, что “по своей природе” можно трактовать не в современном значении – но у меня оставалось ощущение (когда я читал соответствующие труды), что Аристотель считает варваров существами низшего порядка, которые к эллинской “продвинутости” не способны в силу именно природных отличий. Это не расизм (поскольку не про расы речь), но первый шаг к тому, мне кажется.

Аристотель с ключевыми для него понятиями energeia и entelechia (по значению что-то вроде: being-at-work-staying-the-same или being-at-an-end) как раз очень близок к тому, что в новое время сформулировалось в концепции tabula rasa, в частности и в этом его расхождение с Платоном, который много толковал о врожденности знания и трансцендентности идей (хотя тоже не в смысле дискримнации, а скорее наоборот).

I wonder why that picture of Sheba gives her blonde hair. Was it to make her less black? Did the artist not know this was inaccurate? Were the artist under the impression that Sheba was an Australian Aborigine (sarcasm)? The questions abound.

She was seen as very exotic. What can be more exotic than a blue-skinned woman with blond hair? ))

This is my favourite pic of her: http://www.zazzle.com/king_solomon_and_the_queen_of_sheba_c_1270_postcard-239677328277757870

A blue skinned woman with purple hair?

Excellent post! I had started following this blog http://medievalpoc.tumblr.com/ a while back which covers people of color in art history. You may find it interesting as well.

Thank you! There’s actually a link to this blog inside my post )

They have a good collection of images over there…

Crazy-interesting article. I never thought about the racial depictions in medieval and renaissance art, aside from the fact that everything is so blatantly whitewashed and antiquity (esp the Gospel) is portrayed in medieval European garb against the backdrop of French castles that to me any discussion of accurate representation of anything seemed moot for the get-go.

The wondrous and wonderful thing about medieval art is that almost everything in it is done towards a certain purpose, or idea, or thought and very few things are left to chance. So, when you have enough objects on the same subject, you can identify irregularities and then unwind the artist’s thinking behind introducing those “deviations” ) The process is pure mathematical logic. Well, almost. It has more fun in it.

Very good look at the topic of black people in medieval art. Apocalyptic triptychs are one of my favorite genres, but I never new they had such racism. You forgot to mention St. Maurice, who was usually shown as black even though there’s no evidence that he was. Have you read Africa’s Discovery of Europe by David Northrup? The first few chapters have a lot of interesting information on black people in art.

Hi, I didn’t forget St.Maurice, for he was not universally accepted as black, with this imagery showing up in just a handful of paintings before the 15th c. Most of his imagery was white. No, I haven’t read the book, and thanks for the tip, I will try to find it!

Yeah, I know that Maurice wasn’t shown as Black until later. Its just interesting that a popular Saint would have a racial makeover like that.